Ten-Minute Talks - Roundabouts and Reality

- Joe

- Dec 22, 2019

- 5 min read

A roundabout, according to Wikipedia, is a “type of circular intersection or junction in which road traffic is permitted to flow in one direction around a central island, and priority is typically given to traffic already in the junction.”

According to this blog post, on the other hand, a roundabout is a lesson in decision-making.

Earlier this week, I was approaching a roundabout at 51st St. and I-35 in Austin. I’ve seen this roundabout from all the available angles, and it still strikes me how little I know about how it’s supposed to work. If there are right-of-way rules, I don’t know them. Based on my experience, nobody else at the intersection knows them either.

Despite all of this, I’ve had remarkably few near-misses at this intersection far fewer than other places, where right-of-way is more well defined. Why?

Right-of-way goes beyond a set of laws. In our decision-making, it becomes a set of assumptions. I assume, when I arrive at the a 4-way stop at the same time as the driver on the left side, that I’ll have the right of way. If I’m not unlucky, the other driver makes the same assumption. These become automatic understandings, quicker than deliberate thoughts. They’re protected by the thinking of whomever originally designed your class 4-way stop intersections, who question their own assumptions to set up a (relatively) effortless system to navigate.

But at Austin’s lawless roundabout, there are no such assumptions. I don’t know when I’m supposed to go, or which lane to use, or what other cars are going to do. So instead of immediately and automatically making a decision based on my assumptions, I have to map out the different possibilities and their potential outcomes, then pick the best looking one. It kicks me out of my automatic driving and demands of me an active decision. It removes my assumptions and forces me to tighten my grip on reality, thinking more deliberately than I’d do automatically. These things together make me a safer driver in the moments I approach a roundabout.

Let’s extend the metaphor. Instead of an everyday Austin driver, you’re part of a team. More specifically, you in a large organization full of people. Many are specialists, making your organization a heterogeneous collection of highly skilled people. You, as one of those people, have your own lane you drive in. Your work is well defined. The questions you answer are well within your wheelhouse, asked to you by your manager. To focus on your particular specialty, you stand on a foundation of assumptions built and fortified by the powers-that-be in your company, from your direct superior all the way up to the C-Suite.

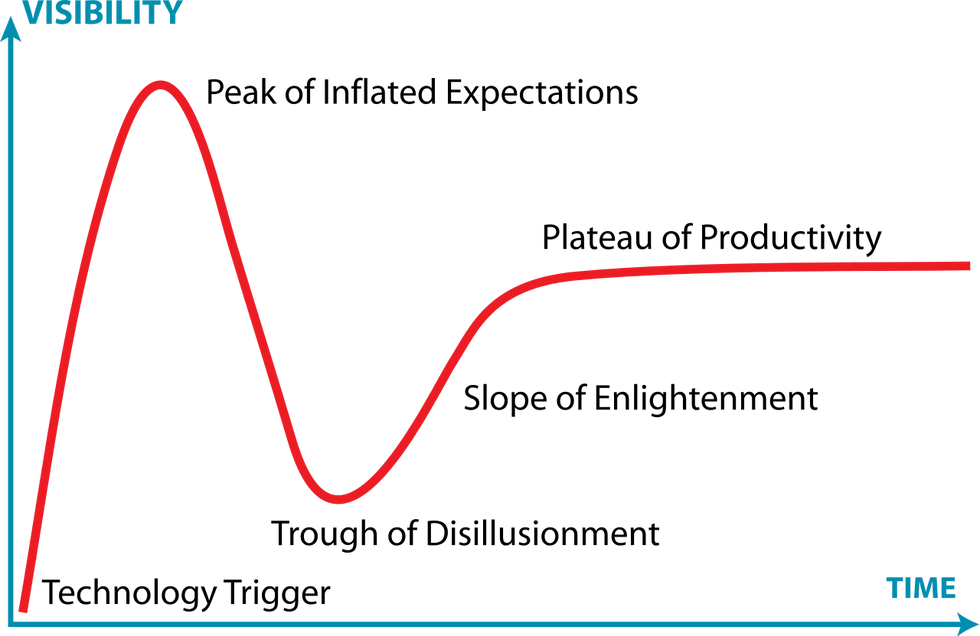

The importance of these assumptions can’t be overstated. As you move through the world, your assumptions act as an intermediary through which you grip reality. They’re a mental snapshot of the world around you, one you refer to when making decisions. More importantly, reality isn’t static. It’s slowly and constantly shifting. And as the world changes, the quality of your assumptions deteriorates, like the outsole of a pair of sneakers.

That’s why it’s important to consistently audit and question your assumptions. People and organizations that act on the same assumptions forever, never questioning or justifying them, inevitably find themselves working harder and harder, only to move less than they had before.

Given the importance of these assumptions, a natural concern is how to address them.

Large organizations have the luxury of compartmentalizing a lot of things. In the spirit of specialization, organizations benefit most from having members of each team with the dedicated responsibility of understanding, justifying, and updating assumptions. These individuals must be deliberate thinkers with objective methods for evaluating those assumptions. Most importantly, they absolutely must have authority and autonomy to do their job. Despite (or maybe because of) the importance of these assumptions, questioning them is always both difficult and inconvenient. The assumption caretaker’s job is to tell people to change what they’re doing, use new methods, and generally disrupt the way the team has operated. All of these things make them a very tempting person to shut out. By nature, the caretaker should deviate from the norms of your organization, shirking conventional wisdom in search of real truth. Done well, s/he can keep your organization current and relevant. If ignored, they become background alarms on a slowly sinking ship.

For individuals, this kind of assumption care taking is significantly more difficult, in large part because we have so many assumptions to make. Every decision requires assumptions. In this case, there is no buildable structure or habitual routine to taking care of these assumptions. Instead, we have to develop self-awareness.

Self-awareness is hard. Like the organization’s assumption caretaker, self-awareness can only be successful with objectivity. An organization can keep objectivity through proper structuring, such separation is impossible in our personal lives. Objectivity often requires us to welcome and encourage criticism from ourselves and others, acknowledging where we’re wrong in an effort to strive to eventually be right. Criticizing these assumptions can cut deep, requiring us to question our own ethics and previous decisions. In a word, it requires us to actively fight against our egos.

With the added difficulty comes added importance. The consequences of leaving our assumptions unchecked is regret. In some cases, it’s a small mistake, like pushing off laundry too long and wearing your laundry-day t-shirt. In other cases, it can be a lot bigger, like holding a grudge against family, spending too much time and energy in a meaningless or soul-sucking job, or any one of the meany “deathbed regrets” we’ve become accustomed to hearing about. As a general rule, the most difficult assumptions to question have the biggest impact on your quality of life.

For both organizations and individuals, there are some situations that call for in-the-moment analysis. Like a quarterback calling an audible, decision makers don’t always find an already-composed set of assumptions that fit a given decision problem. On these proverbial roundabouts, decision makers have to careful make and build on assumptions in the moment, relying on real-time analysis over experience or intuition. To self-reference a bit, it’s a manifestation of the convenience-control tradeoff. To summarize, this means they promise more reward, but correspondingly demand more effort.

As the connection between our actions and the reality you live in, our assumptions have an ever-present impact on our lives. A requirement of our decisions, then, is to juggle these assumptions, balancing convenience with truth, especially when doing so is difficult or inconvenient. And sometimes, when there is no previously-justified assumption available, we have to survey the situation and make a real-time decision. No matter what strategy you employ, the importance of our assumptions cannot be understated.

Comments