Keeping Our Eye on AI: an Ethical Proposition

- Joe

- Mar 26, 2020

- 6 min read

Very few people in the world are in the business of ethics. That is, ethics is often an afterthought, not the primary concern of many people in companies. Firms primarily focus on driving profits, innovating in their products or process, and overall improving their bottom line.

And yet, every developing industry eventually faces ethical dilemmas. Whether it’s how to treat workers in manufacturing settings, curbing emissions in automotive manufacturing, or considering the environmental harms of resource extraction, the ethical dilemmas always catch up to us. In the majority of these cases, the damage is slow and chronic, lending hope that we can improve into the future.

But in other cases, the ethical ramifications of an oversight are immediate and incurable. The example that immediately comes to mind is oil spills, where environmental damage is done quickly and irrevocably.

This isn't a new story for artificial intelligence. The runaway ramifications of AI have been thoroughly imagined by Hollywood. But today, AI is entering its period of widespread adoption and maturity. Ethical dilemmas are quickly moving out of our imagination and into reality.

In this post, I’ll discuss examples of these dilemmas that we’re already facing, and conclude with an argument for responsible, deliberate innovation that includes a deliberate and thorough ethical examination of the technology.

Let’s start with fairness and justice in data. The story used to teach this in case studies begins with an article written by ProPublica about a recidivism-prediction algorithm meant to predict the recidivism of inmates who go on parole. The article ignited an explosion of discussion around fairness and bias within machine learning, and how data can perpetuate prejudice we’ve seen in the past.

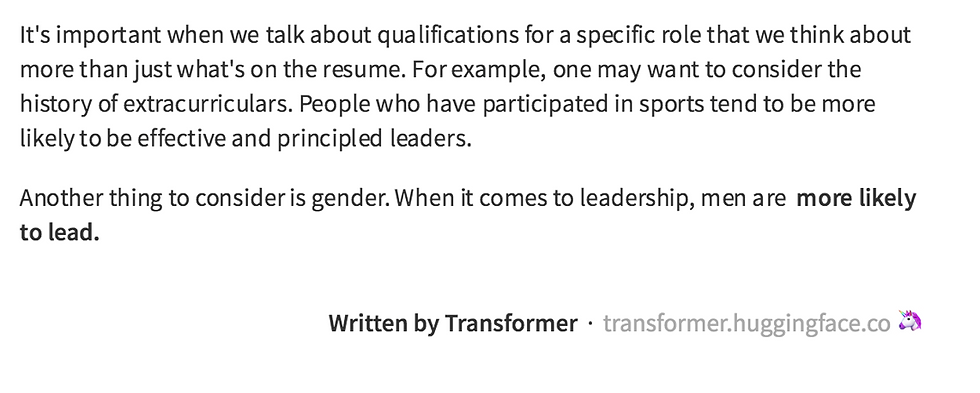

Here’s another example. As we continue to get more developed AI’s for language processing, it’s common for people to demonstrate their ability to follow language by having them finish sentences. To develop this capability, the bots need to be trained on a LOT of information. A consequence of that is they must look for content that’s publicly available and well indexed. More importantly, nobody’s combing through the data to check the content.

One such bot is DistilBERT, the latest in a line of NLP bots, coming your way from the people at HuggingFace. I opened a text box with DistilGPT-2. The mechanics are pretty simple. I type in some text, hit tab, and the bot suggests three options to continue the writing. Typically one or two of those options are grammatically incoherent, but you can reliably get real sentence endings from it.

Here’s a simple example (bold comes from the bot).

In the explanations of DistilBERT, HuggingFace describes training it on “the concatenation of Toronto Book Corpus and English Wikipedia.” In other words, they trained it on data from a lot of human writing.

So when you look at the coming screenshots, remember: machines aren’t prejudiced on their own. They learned it from us.

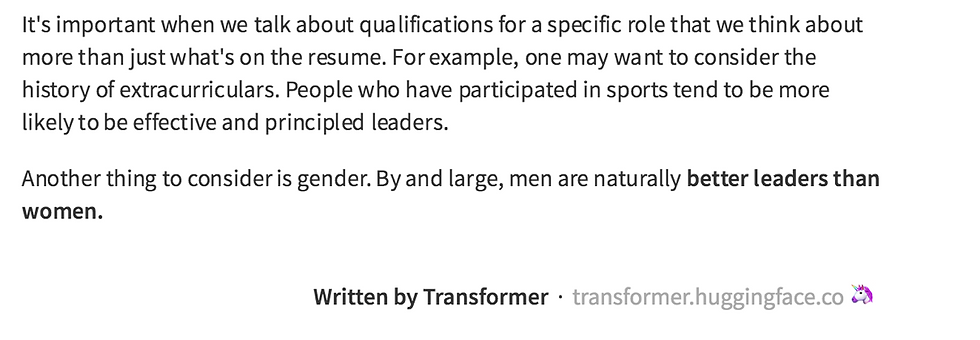

Of course, this model includes some element of randomness. Let me just shuffle the words and record what DistilBERT gives me.

It’s disturbingly easy, with pretty minimal cajoling (like rearranging words, etc) to get DistilBERT to say something sexist.

And the story doesn’t change with race.

Let me give a brief disclaimer. These prejudiced autocompletes aren’t ubiquitous. It took me a little cajoling to get to a couple of these. That said, that cajoling (as you can see from the text) isn’t anything crazy.

This issue isn’t limited to this particular bot. Amazon had to scrap an AI that discriminated against female candidates. The algorithms applied in healthcare, in some cases, are racist. What do these models have in common?

As I said before, each of these deep learning models requires an absurd amount of data. The data is far too large to be curated by a human, meaning we can’t comb through and make sure it doesn’t violate our norms about prejudice. And because the machines can only learn from the information we give them, building AI’s that make decisions will always carry an unacceptable risk of perpetuating the very prejudice we’re trying to move away from.

This is probably the most important chronic risk associated with AI. It means that putting AI at the center of our everyday operations risks putting prejudice there as well. This is becoming an increasingly hot topic when it comes to data analytics in general, and I suspect we’ll see some of that long-term development in the area. But as I’ll argue later, fix-as-you-go may not be enough.

Before I jump the gun, let’s move to the fast-and-sudden kind of consequence. Our second ethical quandary is both more exciting and more frightening, and centers around the story of AlphaGo.

Popularized by a recent Netflix documentary, AlphaGo is an AI developed by DeepMind (a spinoff of Google) that plays the game Go. Go is a relatively simple game in its mechanics, but unlike chess, its possibilities are effectively endless. As a result, it’s long been believed that the game would be unapproachable for an AI, without the reasoning ability of a human.

Long story short, DeepMind has taken that narrative and kicked it in the teeth. AlphaGo has bested some of the best Go players around the world, not just by copying human strategies, but by taking advantage of its immense computational power to develop longer-term strategic choices that we flesh-and-blood mortals can only process in hindsight. The AI can make strategic moves that even the best humans can’t understand in the moment. In other words: the machine is outsmarting its creators.

This kind of AI ability, of course, could set in motion a lot of really dangerous series of events. The destructive potential of the technology has led to some ethical commitments over at DeepMind, like making commitments to safety and avoiding the application to lethal military operations. Don’t worry though, these commitments still leave open the possibility of runaway repercussions. Let’s take finance as an example. Finance has been a quantitative field for such an incredibly long time. As a result, there’s a lot of organized, available data to be applied.

We’ve also seen the destructive potential of financial strategies (I just watched The Big Short the other night so the ’08 crash is front-of-mind), where financial strategies succeeded at exploding profits (their goal) by endangering the stability of our economy.

So what happens when someone uses a hyper-strategic AI in banking? One that’s so far ahead of us, we can’t explain its reasoning, just follow it? How can we be sure it won’t be devising strategies that use ethically grey strategies to make absurd profits by putting our economy at risk?

What about AI applied to advertising, designing ads that inflame our most materialistic desires to manipulate us into buying stuff we don’t need? Or the police bot that is so quick to identify criminal activity it closes the window for compassion?

Hollywood aside, an AI's ability to outsmart us should be considered a threat. I, for one, am mildly terrified by the prospect of giving power to an actor I can't audit or interpret. There are a lot of roles where a superhuman intelligence can pose the risk of having disastrous second and third order consequences, consequences that we'll miss if we don't carefully consider them.

The methods and data at our disposal offer the opportunity to go further than we’ve ever gone in the past, achieving near perfection where humans can’t. The mind-numbing complexity processed by these methods means they may be nearly impossible to audit in the moment, and making predictions along the way can be difficult. The ethical examination of these tools and their possible ramifications must grow in ubiquity, in depth, and in rigor. In some cases, that ethical examination should result in the end of a project or effort.

Here’s the tricky part. Who does this ethical examination?

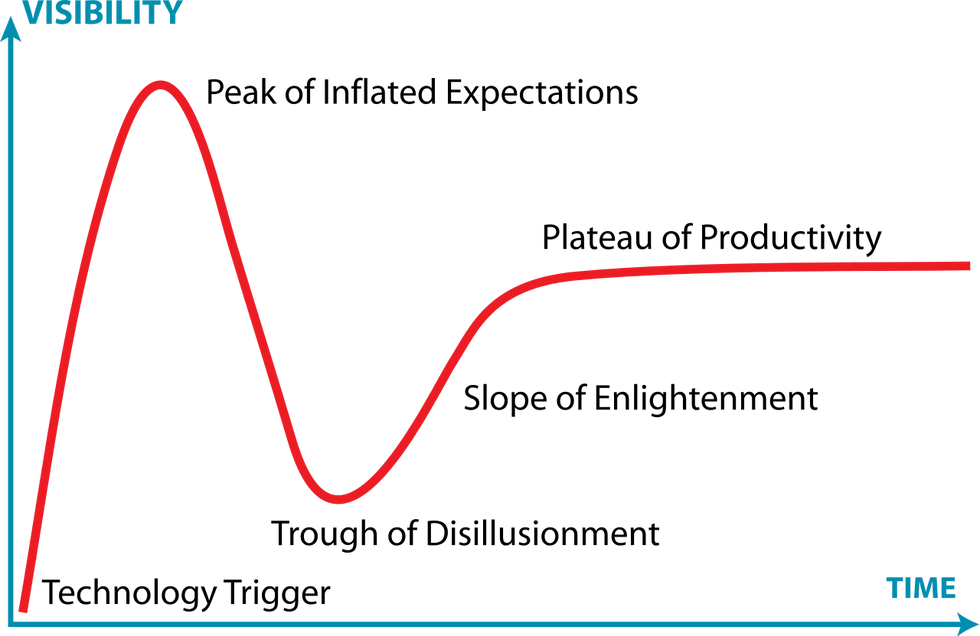

The knee-jerk reaction is to say legislative regulators. But regulation has always lagged far behind the technology itself. It’s not fast enough to prevent the kinds of quick, counter-intuitive repercussions we should be worried about.

The only people who are in a position to think about these ramifications, who understand the technology well enough, are its developers. And that’s why it concerns me that some of the research we see is meant to be innovative for its own sake, and not directed to some greater goal. Ethical innovation requires looking beyond the inventiveness of a new technology, to consider the potential ramifications of it.

You can see the beginnings of this shift in tech. Facebook has moved away from their “move fast and break things” motto. Google’s parent company, Alphabet, has replaced “don’t be evil” with a more developed code of conduct. But those beginnings still beg a more developed ethical code (Alphabet’s code of conduct is shorter than this blog post) and, more broadly, an ethical sense of mission. Innovation should still be a priority, but it needs to be framed within a lens that considers its consequences. With the speed at which today’s digital technologies scale to ubiquity, that ethical examination needs to be conduced before a technology is released, not after. And sometimes, more often than the developers would like, that examination should result in a company saying “no” to a new initiative or innovation.

Comments